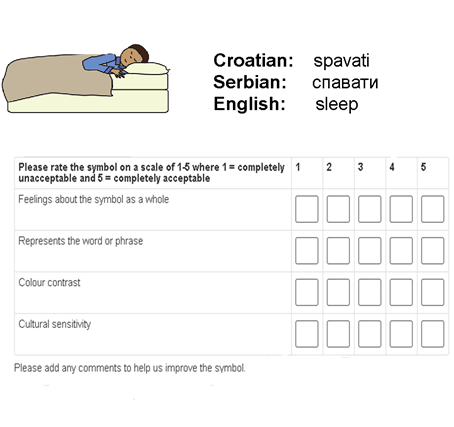

The complexities of creating symbols for communication and the way they work to support spoken and written language has never been easy. Ideas around guessability or iconicity and transparency to aid learning or remembering are jut one side of the coin in terms of design. There are also the questions around style, size, type of outlines and colour amongst many other design issues that need to be carefully considered and the entire schema or set of rules that exist for a particular AAC symbol set. These are aspects that are rarely discussed in detail other than by those developing the images.

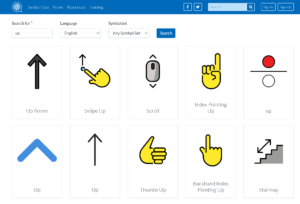

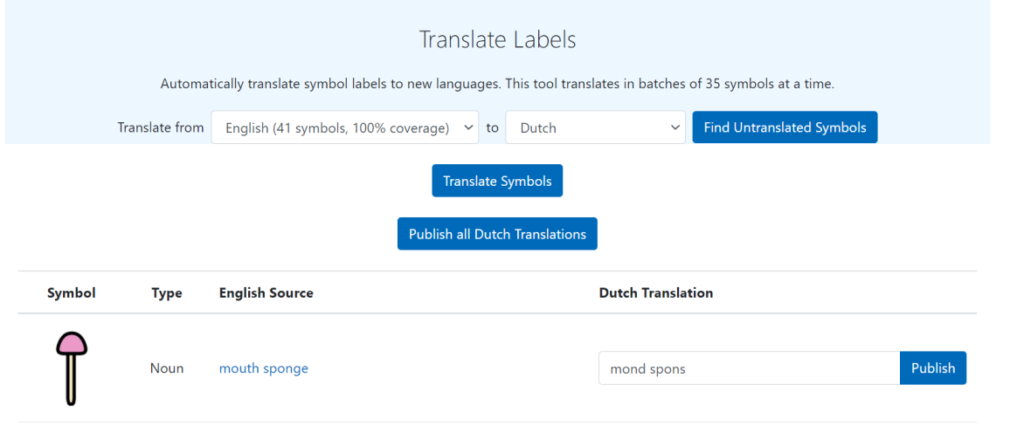

However, when trying to work with computer algorithms to make adaptations from one image to another a starting point can be image to text recognition in order to discover how well chosen training data is going to work. It is possible to see if the systems can deal with the lack of background and other details that normally help to give images context, but are often lacking in AAC symbol sets. The computer has no way of knowing whether an animal is a wolf or dog unless there are additional elements, such as a collar or a wild natural area around the animal such as a forest compared to a room in a house. If it is possible to provide a form of alternative text as a visual description, not disimilar to that used by screen reader users when viewing images on web pages, the training data provided may then work for an image to image situation.

There remains the need to gather enough data to allow the AI systems to try to predict what it is you want. The systems used by Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 have scraped the web for masses of images in various styles, but they do not seem to have picked up on AAC symbol sets! There is also the case that each symbol topic category within the symbol set tends to have different styles even though the outlines and some colours may be similar and humans are generally able to recognise similarities within a symbol set that cannot necessarily be captured by the AI model that has been developed. More tweaks will always be needed along with more data training as the outcomes are evaluated.

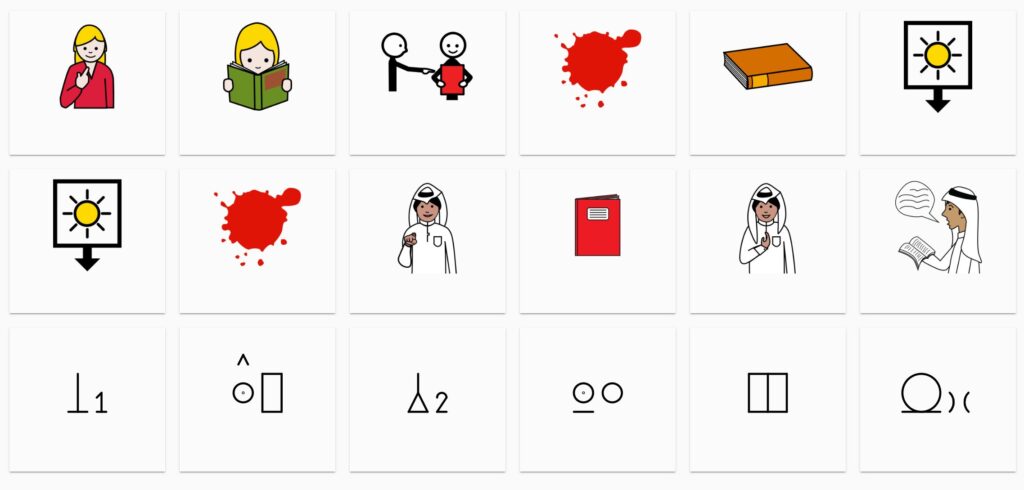

The image above compares groups of symbols from the ARASAAC, Mulberry, Sclera and Blissymbolics sets.

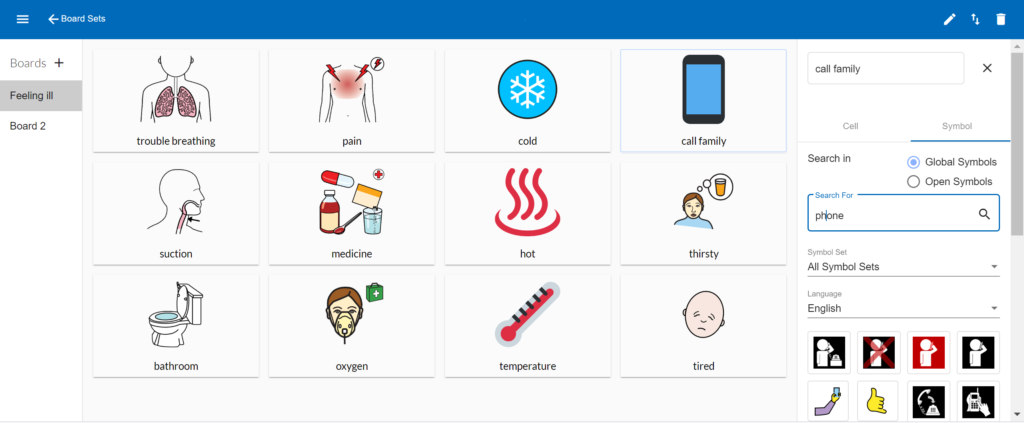

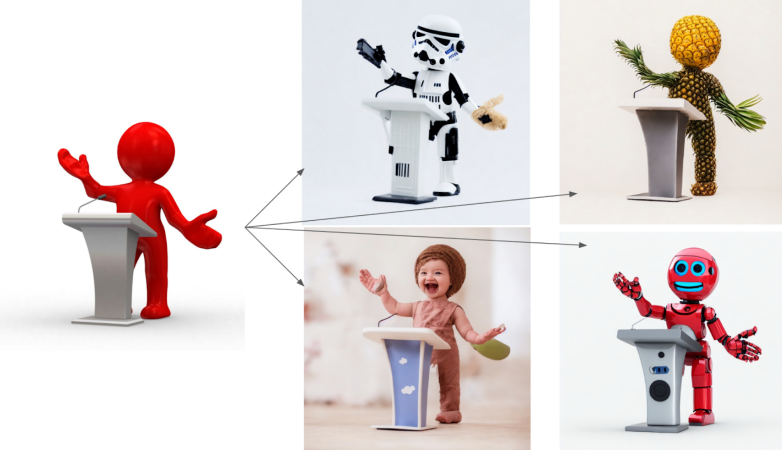

The other problem is that most generative artificial intelligence (AI) systems using something like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 are designed to provide unique images in a chosen style, even when you enter the same text prompt. Therefore each outcome will look different to your first or second attempt. In other words there is very little consistency in how the details of the picture may be put together other than the overview will look as if it has a certain style. So if you put in the text prompt edit box that you want “A female teacher in front of a white board with a maths equation”, the system can generate as many images as you want, but none will be exactly the same.

Created using DALL-E 2

Nevertheless, Chaohai Ding has managed to create examples of AI generated Mulberry AAC symbols by using Stable Diffusion with the addition of Dreambooth that uses a minimal number of images in a more consistent style. There are still multiple options available from the same text prompt, but the ‘look and feel’ of those automatically generated images makes us want to go on working with these ideas in order to support the idea of personalised AAC symbol adaptations.

In the style of the professions category in the Mulberry Symbol set these three images had the text prompt of racing driver, friend and astronaut.

We would like to thank Steve Lee for allowing us to use the Mulberry Symbol set on Global Symbols and the University of Southampton Web Science Institute Stimulus Fund for giving us the chance to collaborate on this project with Professor Mike Wald’s team.

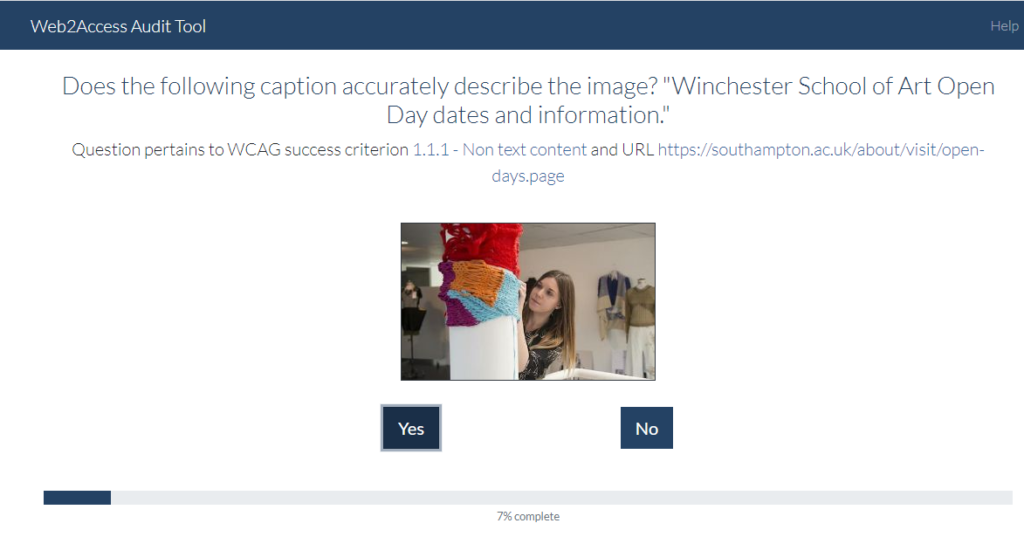

Over the last year there has been an increasing amount of projects that have been using machine learning and image recognition to solve issues that cause accessibility barriers for web page users.

Over the last year there has been an increasing amount of projects that have been using machine learning and image recognition to solve issues that cause accessibility barriers for web page users.  The same can apply to online lectures provided for students working remotely. Live captioning from the videos are largely provided via automatic speech recognition. Once again a facilitator can be alerted to where errors are appearing in a live session, so that manual corrections can occur at speed and the quality of the output improved to provide not just more accurate captions over time, but also transcripts suitable for annotation.

The same can apply to online lectures provided for students working remotely. Live captioning from the videos are largely provided via automatic speech recognition. Once again a facilitator can be alerted to where errors are appearing in a live session, so that manual corrections can occur at speed and the quality of the output improved to provide not just more accurate captions over time, but also transcripts suitable for annotation.